I received this book as a holiday gift from my father-in-law, and liked it so much I want to share my thoughts here. This isn’t a sponsored post.

Yay! I actually finished a book in a normal amount of time (two weeks) – which means I can cohesively comprehend what I read! Ha ha.

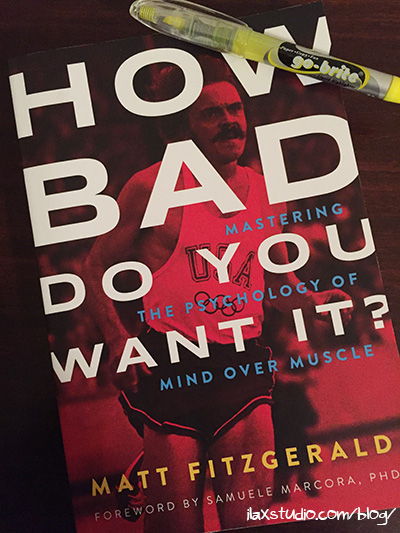

How Bad Do You Want It?, by Matt Fitzgerald, is about how endurance athletes can learn to cope with discomfort and stress while performing, to achieve their best results. The book is heavily focused on the psychobiological model of endurance performance – that the mind and body are deeply connected, with the mind being in charge (as opposed to previous models which believed endurance performance was mostly biological, not psychological).

Well, that makes sense, right? Our brain runs everything! But it’s more than that – it’s the concept that in order to become a better endurance athlete, it’s NOT so much actual effort you have to learn to deal with, but perception of effort – how your brain reacts to what you are doing. Only then, can you push yourself further and further to your limits.

IF you want to. I mean, the title of the book is “how bad do you want it?”!!! I know I’ve been in races and given up toward the end, deciding I didn’t want what I was going for (and truly not being upset about it). I’ve been beaten out of first place (in age group and overall) by less than 10 seconds a few times and said to myself – “yeah, she wanted it more than me and she worked for it, good for her!”

But… what about when you DO actually want it bad enough to go for it?! This has happened to me as well (thankfully, ha) where I had my mind so set on something that I pushed for it and got there – and if it’s happened to you, you know it’s one of the best feelings in the world! This book is about how to achieve that.

The book is twelve chapters – an introduction and conclusion, and ten chapters in between, each one going over a different coping (with the pain of working hard) mechanism, using anecdotes about endurance athletes from the past forty or so years.

I like that it was anecdotal. Stories tend to stick with me – I remember the examples from them better than reading straight up research. And each chapter does have a lot of research in it – but sandwiched between the story (each chapter seemed to start with the story build up, then there’d be the research-y/science-y stuff, then you’d get the conclusion to the story, after).

I did NOT like the goofy analogy throughout the whole book of endurance training being like a fire walk – you know, when people walk on hot coals. That’s just not relatable to me. It felt cheesy and forced.

I also thought it was funny that Pre is on the cover, but he is not even brought up until the final chapter! I was getting worried he wasn’t going to be in there at all!

But the book was definitely effective. Since reading it, I’ve already thought to myself during workouts, “how bad do I want this?” to push myself a bit more. I think I’ll review each chapter’s “coping mechanism” and my highlighted notes from time to time, to see if I am retaining what I read… and if I am using it!

I ended up highlighting a ton of passages! Here are some of them (items in italics are my notes):

- One cannot improve as an endurance athlete except by changing one’s relationship with perception of effort.

- Bracing yourself – always expecting your next race to be your hardest yet – is a much more mature and effective way to prepare mentally for competition. (as opposed to hoping the race won’t be a hard effort)

- Regardless of how an athlete chooses to train, her training will yield greater improvements in race times if improving race times is the explicit goal of the training process. A bit, “well, duh,” but you have to plan to improve, to actually improve.

- The amount of effort that an athlete puts into a race is influenced by her perception of the attainability of her goal. If the goal seems attainable, you will push harder to reach it, during the race.

- As an athlete, you’re much better off directing your attention externally, to the task at hand, which distracts you to some degree from your suffering, allowing you to push a little harder.

- Distinct from mental rehearsal, or practicing a sport in the mind at rest, which is proven to enhance performance, fantasizing about desired outcomes is a maladaptive coping skill be associated with lack of confidence in ones’s ability to make these outcomes happen through one’s own efforts. I thought this was really interesting – make sure your mental work is not just fantasy!

- Counterintuitive though it may be, caring a little less about the result of a race produces better results. This has definitely worked for me, time and time again.

- In psychobiological terms, sweet disgust enhances performance by increasing potential motivation, or the maximum intensity of perceived effort an athlete is willing to endure. Sweet disgust is the angry resolve one has to do better, after many failures. It lets you use your anger to fight back, in a healthy way.

- The coping skill that is required to avoid overtraining is self-trust.

- When people work together, their brains release greater amounts of mood-lifting, discomfort-suppressing endorphins than they do when the same task is undertaken alone.

- Believing one is good at something can elevate performance, independently of actually being good at it.

- The fitter a person expects to get from an exercise program, the fitter he really does get.

- People who have a positive attitude and sweat the small stuff tend to age slower and live longer.

- Passion enhances psychological well-being in ways that are sort of like a personality makeover. People who have a strong passion for an activity are known to spend less time in age-accelerating emotional states such as anxiety, just as naturally positive people do.

- While scientists have found that these brain systems work the same way in all healthy individuals, they have also found that the things people value are highly individual, especially where abstract rewards – such as those associated with the personal meaning an athlete attaches to trying his or her best – are concerned. How hard you are willing to work in a race depends on what the race means to you.

This sounds really interesting! I should pick up a copy. I know I could use a lot of practice with mental training and coping techniques as I prepare for my hardest marathon yet!

Exactly! Let me know if you pick up a copy, and what you think! 🙂

Man that Fitzgerald guy keeps writing interesting books! One of the passages that jumps out at me is “If the goal seems attainable, you will push harder to reach it, during the race.” This seemed to work really well for me my PRs at the “Hot Chocolate 15k” and “4 on the 4th”, where I knew (based on the race conversion tables) that I had exactly enough fitness to achieve my time goals. The mile splits involved in hitting these goal times were daunting, but I believed in the tables and therefore knew my goal were attainable. There were parts of the races where I struggled, but kept believing in my fitness to carry me home. However, this hasn’t worked out so well in the marathon distance, as I haven’t achieved my goal times despite having the requisite fitness. As far as “How hard you are willing to work in a race depends on what the race means to you” goes: I am willing to work hard in a marathon to achieve my goal time, but for some reason, during miles 23 to 26.2, my legs don’t cooperate with my mind!

Doesn’t he? It made me want to get out my copy of Racing Weight, but it’s packed away in the very back of our storage space, LOL!

It’s interesting about the goal seeming attainable – because it’s based both on training and knowing you can do it, but also on that mental knowing you can do it, which I feel is a bit different. And probably makes no sense how I wrote it. Ha ha. But you have to have done the physical training and the mental training. The marathon is SO dayum tricky. So much can happen!

Sounds like you need to work on 23 to 26.2… somehow! Are you running Chicago again this year?

Fascinating stuff, especially the idea of “bracing yourself” – that seems counter-intuitive to me – I always hope it won’t be so bad!

RIGHT? That stood out to me right away, too! I actually train for 5Ks hoping they will suck the least amount of time. Have I been doing it wrong? LOL.

This sounds like an interesting read, though I always wonder about naturally gifted (maybe Fitzgerald isn’t? I don’t know.) writing books for “normal” fitness enthusiasts. There just seem to be so many factors at play to determine one’s performance and fitness. That being said, all the points you summarized make a lot of sense to me. I was surprised about the “external” focus though; I remember an article from RW a few years ago that said that faster runners and elites tended to focus on how they were feeling, rather than focusing on external factors.

Ha, in the beginning of the book, he talks about his workout achievements and areas where he’s given up, so I think he doesn’t think of himself as naturally gifted. And really, whether you are or not, the “coping mechanisms” the elite endurance athletes use are ones we can use, too 🙂 All his examples are elites, but I could see how most of them could apply to me. So… it worked for me! 🙂

I was surprised by that too! The articles DO always say that! I think the point was to notice your environment and where you are headed and don’t get stuck in the pain.

“Counterintuitive though it may be, caring a little less about the result of a race produces better results”

This has been SO TRUE for me for the past year. I’ve hit quite a few PRs on races I didn’t even have time goals for. I just wanted to run hard. I rarely even look at my Garmin anymore when I race. I mean, I still want to do well, but I don’t stress out about it. Seems to be working!

That’s awesome that it’s working for you! I read a blogger who hasn’t been using her watch, and that seems to be helping her, too!

And I think, really, not making the end result be the only thing you get out of the day is ALWAYS a good thing. The people who get so upset about missing a goal worry me. LOL.

I’ve definitely been in at that place at the end of the race where I just stop caring. I feel like I’ve done all I can do. Many times I’m on the verge of puking so maybe I have, haha!

I like Matt’s books, although his idea of racing weight for me is ridiculously low. At least I think it is.

LOL! That is usually a good sign (that you’ve done all you can), I think! 🙂

When I read that, I thought the same thing about my personal racing weight. I seem to carry more weight than standard for my height, and his number seemed way too low.

I must read this book. Thanks for reviewing it- it sounds really interesting. I like books that talk about the mental aspect of performances- athletic or musical. If you enjoyed this type of topic, I’d recommend the “inner game of tennis” which also talks about the mental aspects of achieving goals. It’s been a long time since I read that one, so maybe I should pick it up along with How bad do you want it and compare them 😉

The walking on hot coals thing is something I cannot relate to either. But the other comments you made about the book seem to sum it up as simply “think you can do it and you will have gains” or just be positive since being negative and full of anxiety doesn’t help you achieve goals because it is a waste of mental and physical energy. It was nice to see him make the distinction between visualizing the race and how you want it to go (being helpful for performance) vs just fantasizing about a goal (not helpful).

I think you would definitely like it! I will have too look in to Inner Game of Tennis, too! What musical books have you read on the topic?

YES! You figured out one of the main points – you have to be positive! While reading it, I was thinking of people I know who are always so down on themselves and their training and how they should at least read that chapter!

I liked that distinction, too. Visualizing and fantasizing are NOT the same thing, and that goes with A LOT of goals in life. They say that about weight loss too – that people who spend more time fantasizing about it are less likely for it to happen!